Note- Published in Grassroots Development, the bimonthly journal of the Inter-American Foundation, 1988. This article launched my 2 year prospective oral history of community activism in the colonia Dario Martinez (here given the pseudonym Nueva Casa Blanca), “No One Elected Me, I Just Stood Up” (see preceding post)

THE CHILDREN OF SANCHEZ REVISITED

Mexico City [AP] - Santos Hernandez, patriarch of the family described in Oscar Lewis's best-selling The Children of Sanchez, died when he was struck by a car while on his way to work. He was thought to be almost 90.

- January 5, 1987

Caution! Traffic accidents can be avoided. Afterwards, nothing is the same.

- Road sign on Avenida Zaragosa on the way to Valle de Chalco

With the death last year of Santos Hernandez, also known as Jesus Sanchez , a symbolic if not mythic figure in postwar Mexico has passed away Born in a small village in the state of Veracruz in 1910 - the year that marked the beginning of the Mexican Revolution - it is not surprising that the press should barely notice his demise.

"Jesus was brought up in a Mexico without cars, movies, radios, or TV, without free universal education, without free elections, and without the hope of upward mobility and the possibility of getting rich quick;' wrote Oscar Lewis in the introduction to The Children of Sanchez, published in 1961. " He was raised in the tradition of authoritarianism , with its emphasis upon knowing one's place, hard work, and self-abnegation."

For many in the United States, Oscar Lewis's story of the Sanchez family brought Mexico and the Mexican people vividly alive for the first time. Lewis's use of first person oral histories to present a unsentimental account of urban Mexican poverty was unprecedented in popular anthropological literature. Indeed, issues such as whether Lewis's portrayal of the Sanchez family was distorted by his perceptions as a white, middle-class, well-educated anthropologist are debated even today - several decades later. At the heart of that debate is Lewis's interpretation of what has become widely known as "the culture of poverty."

Based on interviews he conducted in the 1950s, Lewis concluded that the grinding poverty of the Sanchez family and of others like it-a daily reality for people in what is now often called the "informal sector" - cannot be defined only as a state of economic deprivation, disorganization, or the lack of some specific thing . It is "positive in that it has a structure, a rationale, and a defense mechanism without which the poor could hardly carry on."

According to Lewis, the culture of poverty is a persistent condition, a remarkably stable way of life that is passed down from generation to generation along family lines. Unemployment and underemployment, low wages, unskilled occupations, child labor, absence of savings and shortage of cash, lack of food reserves, borrowing from local moneylenders at usurious rates of interest, and spontaneous informal credit devices all characterize this constant struggle for survival.

The question may be asked whether Jesus Sanchez, the passive paterfamilias living in a one-room inner city slum tenement, or vecindad, remains an archetypal figure in today's Mexico. Or does the current plethora of neighborhood organizations, particularly in the aftermath of the 1985 earthquake , signify a new era for the poor? This wave of grassroots activism contrasts strikingly with Lewis 's description of the culture of poverty, which was typified by family insularity and a lack of trust in government officials and others in high places that extended even to the Church.

Indeed, if Lewis were alive to choose a family that epitomized Mexico City's poor today, he might not look again in the neighborhoods in the center of the city. The sociological phenomenon that would most likely capture his attention is not the migration from the countryside to the city proper, which typified the 1950s, but rather the massive growth of newly settled colonias, or shantytowns, at the margins of the city. Recent arrivals there are not absorbed into long-existing urban environments, but rather join the urbanization process from the very beginning, and thus directly influence - knowingly or not - the future of their community.

In the Valle de Chalco, beyond the eastern rim of the city between the colonial towns of Ayotla, Chalco, and Ixtapaluca, Lewis would find thousands of hectares of ejido land - the communal farmland held by the government and leased out to landless peasants after the Revolution. Technically, holders of ejido land, or ejidatarios, are prohibited from selling it, in part to protect the land from speculation and to preserve its agricultural capacity for future generations. In fact, however, thousands of hectares have been sold illegally, and these once-productive fields now support a population estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands.

Lewis would undoubtedly be surprised to find that many of the residents, or colonos, are newly arrived not from rural areas, as was Jesus Sanchez , but from the more urbanized areas of central Mexico City itself-most of them "rent fugitives" escaping inflationary housing costs. What might surprise him even more, however, is the degree of community activism found in at least one of Chalco's colonias . While the "Nueva Casa Blanca" (a pseudonym borrowed from the original Casa Blanca tenement brought to life in Lewis 's book) chosen for this article is perhaps less typical than other settlements, it may be just slightly ahead of its time. The colonos' activism is expressed inwardly through a commitment to self-help solutions. It is expressed outwardly through well-organized pressure on state and municipal governments, exemplified by a recent demonstration at the state capital of Toluca when some 60 residents of Nueva Casa Blanca joined groups from other colonias to lobby for schools, electricity, a water system, and sewers.

"Many of the traits of the subculture of poverty can be viewed as attempts at local solutions for problems not met by existing institutions because people are not eligible for them, cannot afford them, or are suspicious of them."

- Oscar Lewis, Introduction The Children of Sanchez

"Prompt payment for our teachers." "Fixed prices for a barrel of water." "Repair our streets."

"Total electrification."

"Valle del Chalco - an organized community. We want electricity, water, health posts, schools for our children. We call on competent authorities for help."

- Signs carried by residents of Nueva Casa Blanca at Toluca demonstration, August 28, 1987

Nueva Casa Blanca has some 2,000 building lots. About half of them are occupied, most by unregistered owners who bought them directly from ejidatarios or speculators, but there are some renters as well. Where the colonia begins and others end is not immediately obvious, sandwiched as it is between several neighboring settlements. Only its northern boundary is distinctly marked - by a large sewage canal spanned by two rickety bridges.

Like Jesus Sanchez 's inner-city vecindad, Nueva Casa Blanca is a self-contained community It has three pharmacies, where prices are generally twice those in the city proper; a dry goods store; a beauty school, which is now closed; and many walk up windows in private homes where soft drinks, cigarettes, and other sundries are sold. In addition, there is a central market with one stand each for meat, produce, canned goods, and used records. And of greater significance to this article, the community also boasts a primary school currrently under construction; a health clinic established by a private voluntary organization; and a market, or centro popular de abasto, sponsored by the Compaflia Nacional de Subsistencias Populares (CONASUPO) . This government-subsidized collective is locally managed and sells, among other things, discount tortilla coupons, called tortibonos.

"If there's no resolution, we'll strike."

"Let the commission find another solution."

"Don't let the commission adjourn without an answer."

- Chants at demonstration outside the Govermnent Palace, Toluca, August 28, 1987

Nueva Casa Blanca is now organizing itself around three issues of primary concern to the community: education, health care, and food prices. The leadership structure is still tentative, however, as shown by the colonos' emerging political vocabulary Residents all share an intense distrust of those they call lideres, or self appointed community organizers associated with outside professionals and representatives of political parties. At the same time, the colonos have an almost messianic belief in dirigentes naturales, or people who lead by example. As one resident explained, 'A lider tells you what to think, while a dirigente natural acts according to the needs of the community, working for the common good."

There is also a deep suspicion of official negotiations because private deals can be struck between so-called community representatives and the authorities. "Getting too close to officials in order to achieve your goals is dangerous;' explained the manager of the CONASUPO store. "The government pulls at even the best dirigentes naturales and tries to corrupt them ."

Distrust in private dialogue with authorities is so great that during the rally in Toluca, one of Nueva Casa Blanca's delegates would emerge at regular intervals throughout the meeting with the governor's secretary, to update the group outside. Despite this lack of faith in the likelihood of honest representation, however, a three -member CONASUPO committee does exist, and an eight-person school board was recently elected. But they always meet at public gatherings, never in private.

Although it is often difficult to establish the beginnings of " community “ in Nueva Casa Blanca it seems that three apparently unrelated incidents provided impetus for the colonia's burgeoning public institutions - one a family tragedy, one a staple food shortage, and one a casual comment. The final push to build a local school came after a small girl drowned in the canal on her way to another school across the bridge. The CONASUPO store was started when the market in a neighboring colonia responded to a shortage of tortillas by deciding to stop selling tortibonos to customers from Nueva Casa Blanca. And finally, the health clinic was established after the executive director of the Fundacion Mexicana para la Planeacion Familiar (MEXFAM) mentioned to his field coordinator that Chalco's colonias might be suitable sites for the organization's innovative community-doctor homesteading program, which provides subsidies in the beginning but ultimately requires that financial responsibility be assumed by the local community.

Foreshadowing these three somewhat formal institutions, there are smaller, more subtle indications of neighbors talking and working together . Precursors are found in the committees, set up by families with hookups from the same light post, to maintain electrical transformers; in the truckloads of gravel brought in by the community to fill mud holes in the dirt streets; and in the system of launching skyrockets to warn others when a troublesome landlord appears. Despite the obvious benefits of such acts of solidarity, residents of Nueva Casa Blanca have also learned that community activism can have bleak consequences for those who are not care ful, as witnessed by the unresolved murder case that still hangs heavily over the colonia .

"He told me, 'I'm not leaving you anything, but I'll give you a piece of advice. Don't get mixed up with friends. It's better to go your own way alone? And that's what I've done all my life."

- Jesus Sanchez, speaking in the late 1950s about his father

"There are many dedicated people in the different colonias of Valle de Chalco who work for the common good. Their efforts to organize community residents are fraught with problems, however, because they encounter official resistance to, rather than support for, their labors."

-Ramiro Diaz Valadez, from an article in UnoMasUno,

September 4, 1987

In September 1987, Macedonio Rosas Garrido , his wife Rita , and his sister Guadalupe spoke to me about Nueva Casa Blanca, their efforts on its behalf, and their feelings about its fu ture. The testimonials of these contemporary "children of Sanchez;' which are patterned after Lewis's original oral histories, are intended to be more symbolic than representative of new community initiatives among Mexico City's lower class. The conversations, purposely directed toward the subjects covered, were transcribed from tape recordings and translated. The names of the family members, as well as the name of their colonia, have been changed.

MACEDONIO ROSAS GARRIDO

I'm 33 years old and was born in Mexico City. I've got about 10 brothers and sisters living all over the city. One sister lives next to me here in Nueva Casa Blanca. My father died about 17 years ago, but my mother is still living in a little village called Tecama in the colonia 5 de Mayo. I've been married 11 years and have three children, two girls and a boy. I'm an eight-wheel truck driver, but it's been more than a year since I had regular work.

We ended up living here four years ago because we heard that the ejidatarios were selling land. We were interested because we were living in a tenement of about 10 families near San Andres . The building didn't have a name: I think only the older and bigger tenements have names. We were renting there, and twice a year the owners would raise our rent. We started off paying 230 pesos a month and by the time we left, it was up to 1,500. So with a lot of sacrifice, we bought this lot here and built the house, little by little. The cement floor just went down last year.

In the center of the city, life in a tenement is crowded, sad, but here it's sadder still. Over there we had water, sewers, electricity - all the services. Maybe not one or two blocks away, but we had everything we needed, like markets and schools. Out here we have to fight to get an education for our kids, and it's dangerous because the schools are so far away We even battle for water to drink.

Friendships and the sense of solidarity are the same here as there. I left a lot of compadres in the tenement, a lot of friends. I'm very sincere when I make a friend, and I think that when someone is my friend, they're sincere too. When I first got here I didn't know anyone, but then - little by little - I got to know people.

The earthquake didn't do much damage here. We were getting up and the house shook, that was all. Something happened afterwards, though. About a year ago during the windy season between January and March, there were really strong gusts, and wind devils. We didn't have any problems with the earthquake, but with the high winds, yes, we did. In one case a mother was washing clothes outside her house and had left her baby hanging inside in a cradle. A gust came up and took the roof off her house and everything inside it - including the baby.

The ejidatarios, they make money not twice but three times off this land: first when they use it for farming, second when they sell it to people like myself, and third when the government pays them to transfer it back. I don't know any original landowners that still live around here. They all live where they' ve got conveniences like water, telephones, paved roads, and sewers. They aren't going to be so stupid as to come here and suffer after having made out so well selling us the land.

We have to fight for everything. Sometimes it can be dangerous. I really don't know much about the man who got killed because when I moved here it had already happened. My neighbors told me about it. They said he was killed because he was putting up electrical wires for people. You know; illegal hookups to get electricity to the houses. They say nobody had him killed. The men he was working with just killed him because they thought they could charge money for what this guy was doing for free to help the community. Some say the killers got caught and others say they didn't.

Some people are afraid to do too much because of this killing. It's an example. That guy was a government employee, a bodyguard for the ex-president's brother, and he still got killed. What can his neighbors think, who don't have any protection like he had?

In Nueva Casa Blanca there aren't any official organizers ... any politics of any kind. It's simply a battle we're all fighting together - all the neighbors - for the benefit of the colonia. And by the way, we aren't afraid of the authorities as much as of each other. Afraid that somebody among us might propose some dirty business like those killers did. Those guys didn't have any political connections, nothing to do with the authorities, just personal ambition.

What we've got to do is fight together, like we're doing now. We form committees to ask for services for this colonia: We go to Toluca if we have to, or to Chalco or Ixtapaluca, or wherever else we have to go.

There are various groups that maintain the electrical hookups. Each group is in effect the owner of its own transformer box. Some boxes have 10 or 20 families hooked up - ours has 50 - and everyone has to mark their own cable so they know which is theirs. But there's one person in charge of the box, and when he needs money to buy a new fuse or a new main cable, we all pitch in. With our box we've always had cooperation from everybody. Some other guys run their box like a business, and call meetings every week just to ask for more money That's what happened to us at first. One guy appointed himself in charge, and he exploited us whenever he could. Finally we got tired, and chose someone else who does a good job.

I've got this big cistern, but not for any special reason or because I want to make money out of it. In the rainy season the water trucks can't get through the muddy streets, so they don't come. Not everyone has the luxury of having a cistern. Some get their water in SO-gallon barrels, while others, with less money, get theirs in buckets. When it's wet and the people with buckets run out, I give a little to whoever needs it. You know, some people charge 400 pesos for 200 liters and 100 pesos for a bucket. It's robbery because really water shouldn't even cost half that much.

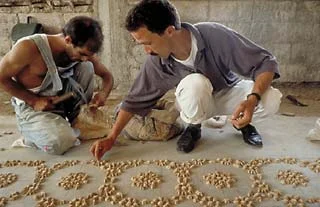

The primary school we're building came from the idea of one person, who told someone else, who told another person, and that's how the idea started taking shape until the moment came that it became a reality It wasn't anything political. We're all cooperating in the const ruction. It's work for men, but to finish the school, the mothers do some heavy work too. They work side by side with the men.

We have plenty of labor but no capital to buy materials. We give what we can - 100, 200, 500, 1,000 pesos - but you must realize, it's a real sacrifice. We're using pieces of old wood and used cardboard. We've already got seven temporary classrooms, but I hope to God that the winds don't come up early, because then we'd lose these rooms and everything. By the time the windy season starts, we've got to have the classrooms more secure.

You see, we're humble people here. We've barely got money to eat so it's impossible to finish the school right. Maybe over the long term, if we build two classrooms a year. We still hope the government steps in. But if the government says no, we've only got our own resources to work with, which are very low. Yet little by little, maybe one classroom a year....

"Almost 20 schools are built each day. The 1982-86 Administration."

- Road sign on Avenida Zaragosa outside Ciudad Nezahualcoyotl

I don't believe it! Imagine! To say they' re building 20 schools a day is crazy You can't believe it. In Mexico City there are millions of people, but if they build 20 schools a day where is the city going to end up? It will be pure schools and no more people. Oh, in the whole country? Well, it still seems exaggerated.

The school still doesn't have a name. For the time being, we call it Nueva Creaci6n (New Creation), not because that's its real name but because it's brand new. The children are going to choose its name. It doesn't have to be named after someone from Mexican history either. The old school is named Simon Bolivar, and he doesn't have anything to do with the history of Mexico. And the other school is named Beethoven, and you know perfectly well that Beethoven isn't famous because he did something for Mexico.

The owners are still a threat. We're afraid they might come by, not to take back the lot, because that's impossible now that we've petitioned the authorities , nor to steal our building material. What we're really afraid of is that they'll come for revenge and burn all the laminated panels we put up as a temporary roof. They'd go up in a second. But we won't have to worry once the real roof is in place.

And the skyrockets? Well, we bought them because we had other problems with the landowners. We took over big lots for the kindergarten we want to build next so there'd be plenty of room, and we did get some threats. So the skyrockets are in case of an emergency if they come to take back the lots. We shoot the rockets off to pass the word to all the parents to come to the school and stop the owners from harming our children.

We haven't had to use the rockets often, thank God, only once or twice. We' ve never had to fight or anything . Only confrontations and arguments. One owner is all right and the other is really negative. They have threatened us with legal proceedings, and one came waving some papers in our faces, which he wouldn't let us read. So we ignored him. And once he brought a lawyer , and a photographer who took our picture and said everyone in the picture would go to jail.

When the government gets around to our petitions, we're ready to support the owners if they have supported us. We' ll go with them to the authorities so they get other land in compensation for what we're taking for the school. We don 't have the power to give it to them ourselves, but we realize that they could lose all their rightful inheritance. If we don't go in a committee to speak up for them , they could lose their land.

GUADALUPE ROSAS GARRIDO

I'm Macedonia's older sister by nine years. I've got three grown children and two grandchildren. I'm with my husband here and my youngest daughter, who's 18. We moved out from Mexico City three years ago after Macedonio told us they were selling land for less than we were paying for rent downtown

I'll tell you how we got our CONASUPO store. They began selling tortibonos at a store in another colonia named lndependencia, at 64 pesos for 2 kilos -the same as it is now. In other places the price for 2 kilos was 130 pesos. Today, without coupons. 2 kilos will cost you 200 pesos. We used to go to the store on the other side of the red bridge at the highway. But sometimes they wouldn't have enough for everybody, and then they told everyone from Nueva Casa Blanca that they couldn't sell to us anymore.

When I first moved here, before the coupon system began, there was another CONASUPO store in Nueva Casa Blanca. It had been opened along with stores in four other colonias, but they all finally closed. Ours had a problem with the woman in charge. She acted as though she was the owner. People didn't like that, so they stopped going.

We all learned that we needed someone with the right personality to run the store this time, someone who wouldn't call himself the boss. And by fighting and pushing and doing whatever took away our silence, we learned we could succeed, not just with the store but in other things, too.

Let's say it was the start of getting to know each other and learning about everyone's problems, not just financial, but social and physical too. Trying to open the store became a way to communicate. It was a basis for better financial and community support for everyone. That's how you learn about yourself, and acquire the respect that self-respect deserves. One of the best ways to find out what people need is for them to go out and look for it themselves .

"The desire to know and to demonstrate that one knows is born in the heart of man."

- Benito Juarez, inscription at the Secretariat of Public Education

Mutual needs you see and live and feel are what help you join with others. There isn't any organizing here, rather we're a group. We've united to move forward toward finding and solving our common needs. Before, we didn't have an organization. Each of us lived our own lives. We didn't see each other: nobody knew who was who, not even each other's names. Everyone kept their needs inside. But once we had the store there was something to talk about. Thanks to that store, we've gotten the courage to tell the authorities about what else we need.

And then we had the idea for the school. We fought, marched, went to see the authorities. But they paid no attention to our petitions, so we now propose to insist on what is ours. What's the difference between requesting and insisting? "Request" is to ask for something that has been promised, and then you keep on waiting. "Insist" is when you see a lot of promises that are never delivered, then you protest . . . and march. That's our way of insisting so they will listen to us.

We hold meetings every Saturday morning at 10 o' clock. Dona Carmen and Dona Zenobia and I are on the CONASUPO store committee. Everyone comes to those meetings. That's how we began to talk about the school. The salary for the store manager and the money for the rallies, to take petitions to the authorities, come from the store.

Yes, I feel like an example for others because, more than anything, we all should be like this. Not to get ahead of the others, no, but simply to be decisive, to know how to talk, to write, to make our needs known. Because if we women are silent, or don't speak up, the authorities will never listen to us, and women will never be treated well. Women should have the same rights as men.

Before, I was very tied to the home. I was the first that tried to get tortibonos at the Independencia store, and I told some of my friends here about them, that I wished we had tortibonos here. That's how I was accepted by these people, and they listened to me. That's when I decided to get more involved, to help my colonia a little more, and me too. And until now I haven't felt like stopping, not until what we want is achieved.

I've made new friends. I've been accepted by some people and rejected by others, but I don't pay attention to the rejection, I just keep on fighting because you have to realize that we have a lot of jealous people in this colonia, people that really don't care about the well-being of others. They're conformists, without any desire to improve themselves. Some are among the first people that moved here, others are new. Maybe they don't have any little ones who risk their lives going to school, or they're just backward. We don't ask their support, but we also don't want them to drag us down. They see the school, our sacrifices as parents, and instead of being quiet they're against us. A lot of parents are under their influence ... well, maybe just a few. The rest of us have decided to carry forward without paying attention to them.

No, I don't feel proud of myself, just satisfied. Nothing more than that. Not proud, because I don't have any reason, because we're equal here. But satisfied, yes, in seeing that something has succeeded in our colonia. I don't think about the present as much as the future because I have grandchildren and I want them to have an education.

RITA MARTINEZ DE ROSAS

I was born in Poza Rica, in the state of Veracruz, and went to Mexico City 15 years ago. Macedonio and I moved out here with the children four years ago. My sister lives in this colonia, too. She's a store cashier and helps us out sometimes. The money I make selling comic books at the school isn't very much. Out here nothing's certain, that's for sure, but it's a little better now that the school is being built. Now the children won't have to walk so far.

"To buy school supplies, parents must pay 25,000 pesos per child - the equivalent of one-and-a-half times the monthly minimum wage!'

- from an article in El Excelsior, September 2, 1987

What do I know about the MEXFAM clinic? I know its specialty is family planning, but they also give general exams and attend to children. The doctor treats everybody Most days there are a lot of people to see him-at least 15 or 20-and they come from other colonias too. The doctor helps the community a lot because he's the only one we have. We still don't have a doctor on duty both day and night. My little girls sometimes have sore throats and diarrhea. It's very common here because we have no water system.

If the doctor's able, he gives us medicines for free because the pharmacies charge so much. Everyone else pitches in too. If someone brings medicine back from the free pharmacy at the social security hospital and doesn't need it, they give it to the doctor to give to someone who does. He charges very little compared to others, less than they charge at the government clinic in Ayotla, plus that clinic is so far away.

MEXFAM brought the doctor here two years ago. When the clinic first started th ere was a lady doctor, now we've got a man doctor. Sometimes his sister comes. She's a dentist, and she charges the same as her brother. He's also thinking of putting in a small hospital, with beds for overnight patients and baby deliveries. He wants to get the midwife who lives nearby to cover for him at night. There's a social worker who gets us together to talk about how we can improve our nutrition, to make things better here for our children's health. We don't have a support committee for the doctor, but I think we should.

The tortibono coupons from the CONASUPO store are necessary because there are lots of families here with hardly anything to eat. Some of them have six or eight children, and there aren't enough tortillas or the money to buy them. A family with five people can eat four or five kilos of tortillas a day because we eat them for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. They only let you buy two kilos a day with the bonos. Really, a family with a lot of people needs more tortillas than that.

I buy milk from the subsidized dairy three times a week. We have to go all the way to the other side of the highway. It costs 300 pesos for four liters, and they limit how much you can buy, depending on how many children you have. If you have more than four children you can buy it every day. Still, it would be a good idea to have our own dairy here. Maybe that should be our next project.

About the death of that little schoolgirl, it really brought us together with her mother. When they found her little girl's body in the canal, we saw we all lived here and just how bad the consequences of that ditch can be.

Some anthropologists dispute Lewis's concept of the "culture of poverty" as too restrictive. Lewis, in fact, sometimes defined it as a subculture rather than a culture, and he recorded testimony from his informants demonstrating a wider variety of experiences among the poor. Even if Lewis's conclusions were valid some 30 years ago, the concept today might have to take into account people like the Garrido family. Their openness, their belief in a better future for their children, and their willingness to act on behalf of the community stand in sharp contrast to the individualism and fatalism expressed by Jesus Sanchez .

The community achievements in Nueva Casa Blanca are such that Macedonio Rosas Garrido would never tell his son, as Sanchez was told by his father, "Don't get mixed up with friends. It's better to go your own way, alone.”