Cairo is different, and in the Cairo I know, more than in any other place, the stranger needs a guide, for, though the city’s principal monuments are obvious to the eye, its diversions are transitory and less easy to find, and though the inhabitants may welcome the foreigner with a smile, beware, for they are all charlatans and liars. They will cheat you if they can. I can help you there.

-The Arabian Nightmare, Robert Irwin

I was taking a mid-afternoon, mid-summer, non-air-conditioned nap and awoke from a dream with indigestion. Was it my lunch? Rancid oil in the fryer? Too many pickles? Spoiled white sauce? Damn my ta’miyya- “tasties”, as Egyptians call their falafel- man on the street corner. Poisoned again.

The knot in my stomach was getting tighter, deeper, and higher. It was hard to take a breath without hurting. I had to lock my chest, no twist or turning, if I wanted relief. I figured it was worth walking back to campus, five blocks in the heat, to visit the school infirmary.

The nurse took a look and asked what I’d eaten for lunch. No problem, he said. Chickpeas OK, fava beans bad. He palpated my stomach. Knock, knock. No problem there. Then he palpated my chest. Thunk, thunk. Problem, he said. He gave me the address of a chest doctor, not too far, he said, and I set off into downtown. It hurt less if I walked in a straight line. Good luck with that on Cairene sidewalks.

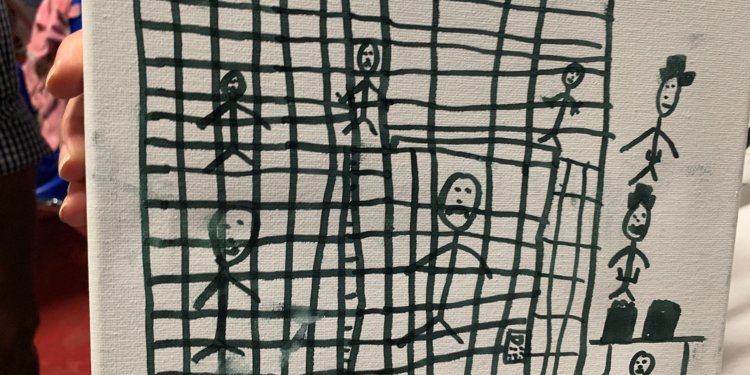

The address was a belle epoque building covered with a mixed up checkerboard of doctors signs, white on black and black on white, that hang everywhere in central Cairo- a city of hypochondriacs, I always thought. Not me. The elevator was out of order and the office two flights up. Oh well, I wasn’t dead yet.

There were a few patients in the first room waiting for the doctor, duktour giraah Gamal Abu Sinna, Doctor Surgeon. His receptionist didn’t speak English but in my first semester Arabic I explained that it hurt. My kirsh, my belly. She read the chit I’d brought from the AUC nurse and took me right in. Khawaja courtesy or emergency? I hoped the former.

Dr. Abu Sinna had a thoracic fluoroscope in the office, what you might see in a Daffy Duck cartoon when he stands behind the glowing screen and you see the hammer and nails he’s just swallowed. When I stood behind it, Abu Sinna couldn’t find my left lung. It had popped and shrunk inside my chest to the size of a plum. Pneumothorax, he said. Istirwah al-sidr, Airing of the Chest. It must really hurt when you breathe, he said.

He said, I’ll see you tomorrow, bukra, in the morning at Agouza Hospital. Don’t eat or drink until then. We must operate. Next, he shouted to his receptionist. I walked out and back downstairs and hailed a cab to my apartment. I hated to think it, but I did anyway. In Egypt, IBM runs everything. InshaaAllah. Bukra. Ma'aleesh.

I was curious about the word hypochondriac, which comes from the Greek word for the upper abdomen, exactly where I was feeling bad. The ancients thought that melancholy and morbid thoughts originated there. Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy said the condition was caused by swallowing too much spittle. After seeing Dr. Abu Sinna, I can say that it is not caused by eating too much ta’miyya. And if melancholy is all in the mind, or maybe spit in the stomach, the problem in my case was altogether different. Air in the chest. And Abu Sinna was right, it really hurt.